Gender, children and missing data: The AGEE project at the World Data Forum, April 2023

By Elaine Unterhalter

Over the last thirty years, there has been a huge investment in just about every country in the world to enhance the capacity of government education departments to collect and analyse administrative data on children at school. Gender has been one of the main organising categories, allowing places and phases of education where girls and boys are present and absent to be mapped. But this big effort around Education Management Information Systems (EMIS) and concern with gender parity in enrolments, progression or attainment, has obscured gaps in these systems, with gender and intersecting inequalities a particular aspect of the omissions. These gaps around data raise questions about whether good enough judgements are being made about, for and with the most vulnerable, the most excluded, and plans for a future that would prevent these exclusions.

Members of the AGEE (Accountability for Gender Equality in Education) project presented on these themes at the UN World Data Forum, held in Hangzhou in April. The Forum brought together an estimated worldwide community of approximately 11,000 people interested in how data can be better collected and interpreted to support the partnerships established to deliver on the SDGs. One outcome of the Forum was the Hangzhou Declaration, which stresses a perception of data as a ‘strategic asset’ and urgently calls for an increase in the level and scale of investments in data and statistics from domestic and international actors. The Declaration highlights the need for public, private and philanthropic sectors to strengthen statistical capacity in low-income countries and fragile States, close data gaps for vulnerable groups, and enhance country resilience, using data to assist efforts to support people through periods of economic crisis, protracted conflicts, climate emergency, increased food insecurity and anticipated future pandemics.

This concern with the gaps in data and the need to build accountable and equitable systems for data governance is laudable, but during the Forum there was only very limited discussion of the specific needs of children and some of the gender issues these needs raise. On a panel convened by the NORRAG Missing Data project, members of the AGEE team (Elaine Unterhalter and Lebo Moletsane) were joined by speakers from NORRAG, the Governance Lab (GovLab), and the International Data Alliance for Children on the Move (IDAC) who highlighted the need to consider some of the unique characteristics of children and the governance issues around data these raised, the ways in which populations of mobile children, and the many subgroups within this, were generally overlooked in official statistics, and the ways historically marginalised peoples, such as indigenous peoples, have not had rights to own and share in the development of data. As members of the AGEE team argued, gender has been understood in very limited ways with regard to data on children, whereby children have been characterised generally in binary terms, as in or out of school, or as male or female. The complex social relations in and around education that form gendered structures, identities, ideas and actions have not been systematically mapped through data, and the experiences and forms of vulnerability of many groups of children are not known or engaged in processes of change.

Dashboards have been one way the data developing and using community has tried to marshal a wide range of information in accessible and transparent ways. Gender and education dashboards such as that developed by the project MHM in Ten (mapping a ten year agenda on menstrual health management in schools), and the Equal Measures 2030 project, and visualizations such as the EGER platform all add depth to our understandings However, Steve McFeely, a member of the AGEE steering committee and currently Director of Data and Analytics at WHO, has written that dashboards are not the answer to everything, as they distil patterns and associations but cannot protect against all accidents and emergencies. For those, we need judgement together with data. In the field of children, education, gender and data, we acknowledge the need for careful judgement about forms of inequality and how to change these, concerns with the safety of children, and improvements in youth participation in thinking about data and its uses.

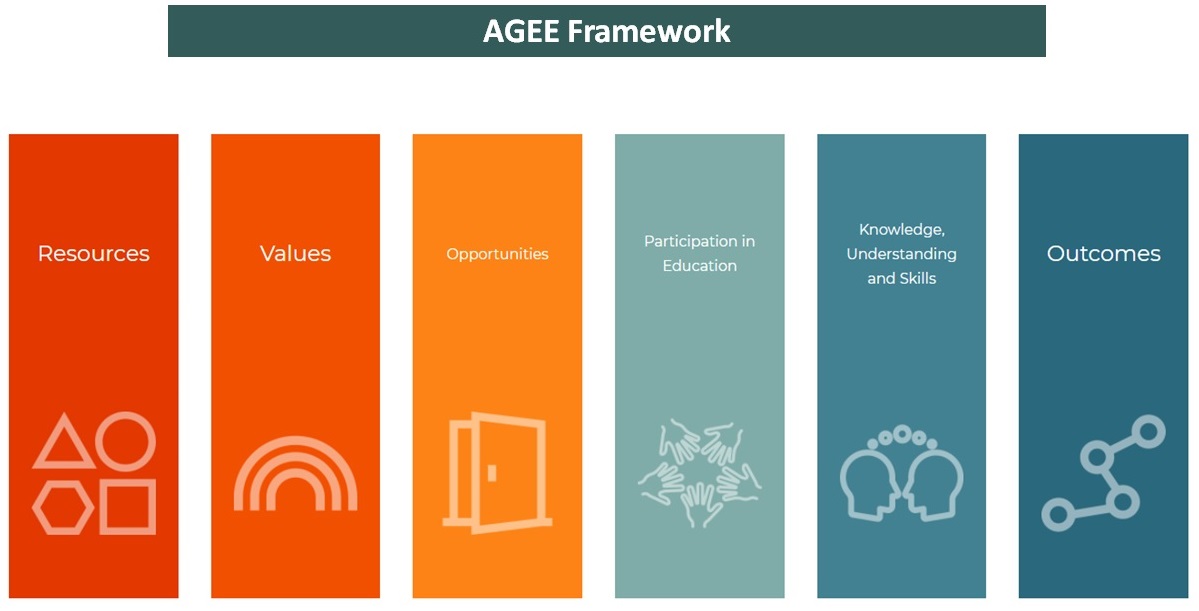

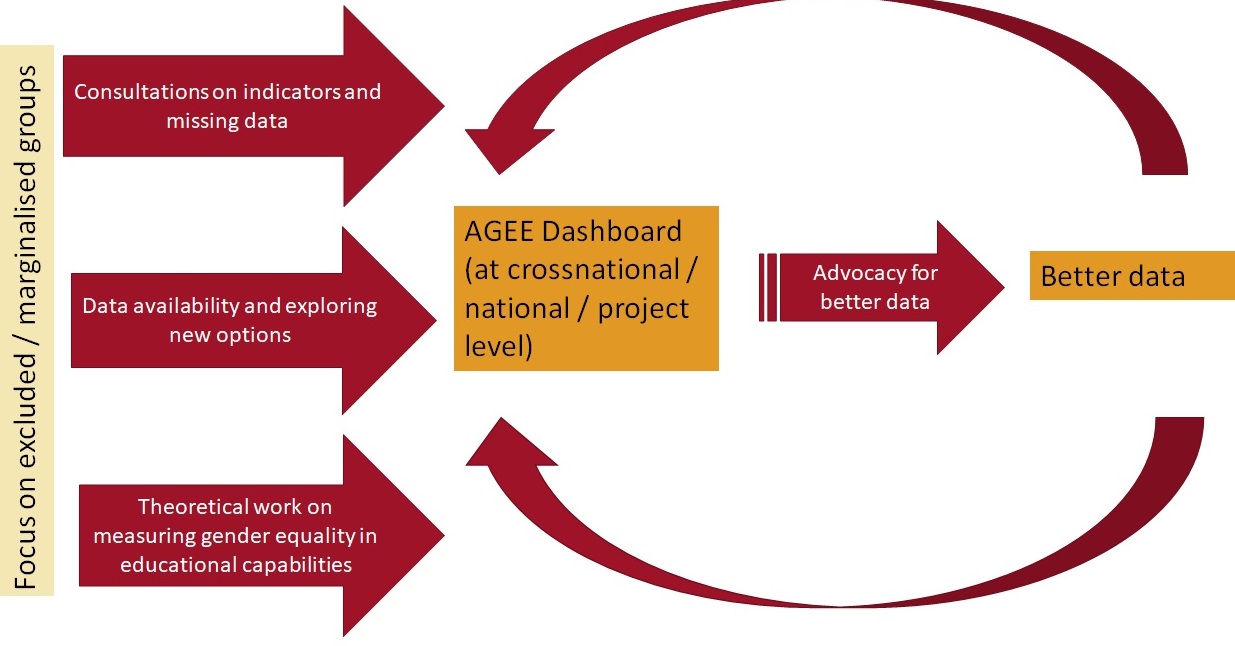

We have tried to build some of these processes into work on the AGEE dashboard, where the process of thinking about data together and building the dashboard is as important as the product. Thus the AGEE approach encourages participatory documentation of the different ways in which gender and other intersecting inequalities shape education-related opportunities and outcomes for children across many different settings. The dashboard is flexible and can be used to build partnerships around reflecting on data and their absence at cross-national, national, institutional and neighbourhood levels. The six domains of the AGEE Framework and the process we have established for thinking about indicators and data, allow for noting both the data we have, what is missing, and what needs to be collected.

The process of reflection we have been using in the AGEE project is distilled in this diagram:

While we are still quite far away from having good dashboards at all these levels and sufficient robust data, as called for at the Transforming Education Summit in 2022. We hope that the urgency of the need to enhance the collection of data and the building of data networks, highlighted at the UN World Data Forum will generate a deepened interest in and engagement with the work of the AGEE project and the community of practice we have built.